How Do You Make Maple Syrup?

The fundamental steps for making pure maple syrup are basically the same as they were hundreds of years ago when the Native Americans first did it and then introduced it to the early immigrants from Europe. The simple description is that you collect sap from sugar maple trees and boil (evaporate) it until it reaches the proper density for syrup. The five steps involved from start to finish are: (1) preparing for the season; (2) determining WHEN to tap; (3) identifying the trees to be tapped and tapping them, (4) collecting the sap and processing (boiling/evaporating) it; (5) filtering, grading and packing the syrup. While the basic steps are the same as hundreds of years ago, new processes and technologies have been developed which have increased productivity and ensured consistent high quality syrup. But the end result is still that beautiful, wonderful tasting amber liquid we call maple syrup. For a full description of the step-by-step process, download the Connecticut Maple Syrup Producers Manual. You may also download a glossary of terms. MSPAC offers a Maple 101 course once a year. If you are interested, contact us.

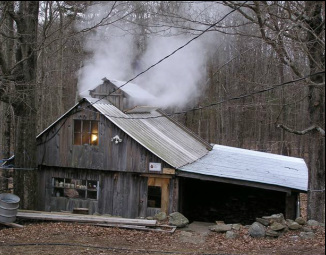

Preparation is critical. Months before the start of the short maple syrup season, the sugarmaker has been preparing for the upcoming spring season. Tasks such as cutting and splitting firewood for the sugarhouse and stringing and/or repairing the tubing in the sugarbush have taken place months before. A final cleaning, careful examination and even testing of equipment is the sugarmakers last task before the start of syrup season. Lack of good preparation often results in a poor season. |

The season is short and subject to weather conditions. The traditional maple sugaring season in Connecticut extends from early February until late March, depending greatly on the weather. Freezing nights and warm, sunny days are necessary for the sap to flow from the maple tree. Sap is a colorless liquid with a light, sweet taste – about 2% sugar out of the tree. It is when the sugarmaker anticipates the right weather conditions that he/she will make his/her determination to tap the trees. Once the trees are tapped, the season lasts for 6-8 weeks until the nightly freeze no longer happens and the sap stops flowing or the trees start to form buds for their leaves. It is then time for the sugarmaker to thoroughly clean and store his equipment until the next sugaring season.

The sugar maple is the primary source for tapping. The most common tree the sugarmaker selects is the sugar maple, Acer saccharum. These trees grow in the northeast quadrant of the United States and around the Canadian Great Lakes. The maple trees the sugarmaker selects must be no smaller than 11 inches in diameter (about 40 years old) to be suitable for tapping.

Once the trees are tapped, it is up to the weather as to when the sap will flow. In late winter and spring sap is flowing up the tree every day but freezing nights and warm days are necessary for the maple tree to yield sap for the sugarmaker. During the day the sugarmaker may check to see if the weather has been favorable for the sap to flow out of the tree. It is when the buckets and sap tanks contain sap that it is time to collect the sap from every bucket and tank, and transport it back to the sugarhouse. The task of collecting sap can have its challenges. It can be difficult to collect sap in a fresh snowfall or when the melting snow turns the ground to mud. Cold temperatures can freeze pumps, valves, hoses, and couplings. To limit these obstacles some sugarhouses are built at the foot of the sugarbush so the tubing can bring the sap from the tree directly into the sugarhouse.

The sugar maple is the primary source for tapping. The most common tree the sugarmaker selects is the sugar maple, Acer saccharum. These trees grow in the northeast quadrant of the United States and around the Canadian Great Lakes. The maple trees the sugarmaker selects must be no smaller than 11 inches in diameter (about 40 years old) to be suitable for tapping.

Once the trees are tapped, it is up to the weather as to when the sap will flow. In late winter and spring sap is flowing up the tree every day but freezing nights and warm days are necessary for the maple tree to yield sap for the sugarmaker. During the day the sugarmaker may check to see if the weather has been favorable for the sap to flow out of the tree. It is when the buckets and sap tanks contain sap that it is time to collect the sap from every bucket and tank, and transport it back to the sugarhouse. The task of collecting sap can have its challenges. It can be difficult to collect sap in a fresh snowfall or when the melting snow turns the ground to mud. Cold temperatures can freeze pumps, valves, hoses, and couplings. To limit these obstacles some sugarhouses are built at the foot of the sugarbush so the tubing can bring the sap from the tree directly into the sugarhouse.

Collecting and processing the sap is a critical step. There are two basic methods used to tap the tree. The classic bucket and spout method and the pipeline or tubing method. The procedure with the bucket and spout method is a small shallow hole is drilled into the tree, a spout is tapped into the hole, a bucket is placed on a hook, and a cover is attached to keep out debris. The procedure with the pipeline or tubing method is a small shallow hole is drilled into the tree and a spout attached directly to the tubing is tapped into the freshly drilled hole. A web of tubing and pipeline runs downhill, straight, and tight for the sap to effectively flow to a holding tank at the end of the tubing pipelines. Larger syrup producers may choose to apply vacuum to the tubing. With the implementation of vacuum a sugarmaker may increase sap yield by two-fold. The vacuum stimulates sap flow from the tree and through the tubing.

Sap should be evaporated soon after it is collected. Once the sap is at the sugarhouse, the sugarmaker must quickly start the process of evaporating the perishable sap. Sap that is not boiled immediately can ferment and produce “off taste” syrup. The boiling usually takes place in a commercially produced evaporator pan that is made specifically for the production of maple syrup. The evaporator rests on top of a firebox called an arch. Many arches are wood fired while others use oil and some even use natural gas, propane, and even wood pellet chips.

If necessary the sugarmaker will keep a hot fire burning late into the night, and in some cases around the clock to boil the sap until it is gone. No matter what is used, the process is the same. Evaporate off the water until the boiling point of the sap concentrate climbs to 7 ½ ° F above the temperature at which water boils, usually 212° F at sea level. The exact specific gravity may be measured with several devices, but to ensure proper density a combination of a thermometer and hydrometer are most often used. When the sap has become syrup, it is drawn-off the evaporator. Often producers choose to finish their syrup on a much smaller pan called a finishing pan. In addition to proper density, the syrup must be filtered, and the color graded before packaging.

Larger producers utilize high pressure filtration to remove a large percentage of water from the sap before it enters the evaporator with a process called reverse osmosis (RO). This process saves the sugarmaker both time and energy. Sap out of the tree averages 2% sugar. RO’s can produce a concentrate with upwards of 12% sugar, while reducing the volume of liquid by 70% or more. Boiling is still required to make maple syrup at 67% sugar.

If necessary the sugarmaker will keep a hot fire burning late into the night, and in some cases around the clock to boil the sap until it is gone. No matter what is used, the process is the same. Evaporate off the water until the boiling point of the sap concentrate climbs to 7 ½ ° F above the temperature at which water boils, usually 212° F at sea level. The exact specific gravity may be measured with several devices, but to ensure proper density a combination of a thermometer and hydrometer are most often used. When the sap has become syrup, it is drawn-off the evaporator. Often producers choose to finish their syrup on a much smaller pan called a finishing pan. In addition to proper density, the syrup must be filtered, and the color graded before packaging.

Larger producers utilize high pressure filtration to remove a large percentage of water from the sap before it enters the evaporator with a process called reverse osmosis (RO). This process saves the sugarmaker both time and energy. Sap out of the tree averages 2% sugar. RO’s can produce a concentrate with upwards of 12% sugar, while reducing the volume of liquid by 70% or more. Boiling is still required to make maple syrup at 67% sugar.

Careful filtering and packing ensures high quality. Filtering may be done with a simple wool filter material through which the hot syrup flows by gravity. Or a filter press can be used forcing 200° F syrup (mixed with diatomaceous earth - an FDA approved filter medium also used in wine making) through a series of filters under pressure. After filtering, the maple syrup is graded by color by comparing the syrup produced to a standardized grading kit.

The four grades of syrup are made by exactly the same process and contain the same amount of sugar. Maple syrup is graded from light to dark into four different classifications: Grade A Light Amber, Grade A Medium Amber, Grade A Dark Amber and Grade B. All four are high quality products made by exactly the same process and contain the same amount of sugar (66.5-67% per FDA definition). The difference in color and taste is determined by how long the sap needs to boil to become syrup (more sugar in the sap equals less boiling time) and the differences in the sap as the season progresses – e.g., the further along you are in the season, the more natural fermentation happens to the sugar in the sap before it enters the evaporator. These, among other factors, are what create the different flavor profiles of the four grades of syrup. Which one is “best” depends on individual taste preferences and how the syrup is used. The grading system changed in 2015. The four classifications are:

The four grades of syrup are made by exactly the same process and contain the same amount of sugar. Maple syrup is graded from light to dark into four different classifications: Grade A Light Amber, Grade A Medium Amber, Grade A Dark Amber and Grade B. All four are high quality products made by exactly the same process and contain the same amount of sugar (66.5-67% per FDA definition). The difference in color and taste is determined by how long the sap needs to boil to become syrup (more sugar in the sap equals less boiling time) and the differences in the sap as the season progresses – e.g., the further along you are in the season, the more natural fermentation happens to the sugar in the sap before it enters the evaporator. These, among other factors, are what create the different flavor profiles of the four grades of syrup. Which one is “best” depends on individual taste preferences and how the syrup is used. The grading system changed in 2015. The four classifications are:

|

Grade A Golden Color: Delicate Taste

Grade A Amber Color: Rich Taste Grade A Dark Color: Robust Taste Grade A Very Dark Color: Strong Taste |

Once the grading is complete, the syrup is packed into containers of the sugarmakers choice at 190° F and sealed immediately to prevent contamination. Product quality is critical. The entire process from collection through filtering and bottling demands the highest quality standards. As a food product, maple syrup must be 100% pure with no margin for error. Download a quality control checklist for more information.