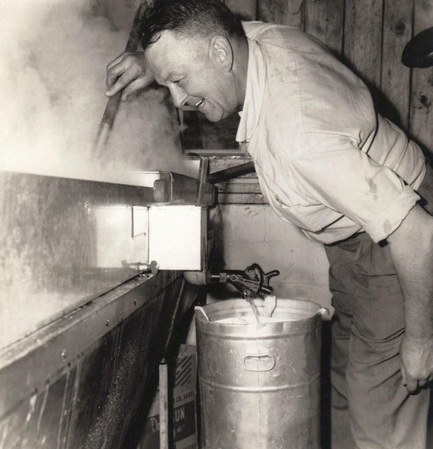

Oliver L. Scranton, Maple Grove Farm, North Guilford (c. 1960). New England winters can be interminable. By the time February rolls around, the skies are gray and the snow is brown. March shows signs of warmer weather as thin sheets of ice stretch across the frozen mud. I understand why some people don’t like this time of year. But growing up, the weeks between Presidents’ Day and St. Patrick’s Day were a sweet, golden amber dream known as maple syrup season. By age seven, I was an integral part of the sugaring operations at Maple Grove Farm in North Guilford, Connecticut. Maple sugaring was a family affair, and each one of us had a role to play. I was the tour guide, and I took my job very seriously. I would show visitors the sap buckets and collection tanks, let them taste the clear, sugar-water-flavored sap and explain the entire sugaring off process. Everything I knew I had learned from my grandfather, whom I adored. He taught me that it was the Native Americans who shared the secrets of maple syrup production with our ancestors, even though there were plenty of sugar maples in Europe. He taught me that the sap runs when cold nights alternate with warm days – and that the sap stops running when the leaves start developing. Finally, he taught me the show stopping statistic that was guaranteed to get a low whistle: it takes 40 gallons of sap to make just one gallon of syrup. While I loved being a tour guide, the best time of day was after the visitors left. My cousins, nine and eleven, and I would go with my grandfather to collect the sap. The two boys would dump buckets of sap into the collection tank on the trailer. I sat with my grandfather, occasionally steering the big green John Deere tractor through the fields. As the sun set, we would finish collecting the sap and head back to the sugar house. Sometimes we’d have pancakes for dinner, with a little bit of hot maple syrup drawn right from the evaporator. Other times we’d have chili or stew – which meant that dessert would be a maple syrup taffy made by pouring maple syrup onto fresh snow and letting it chill enough to become a sweet, flexible treat. My grandfather died in 1984, a few months shy of my tenth birthday. As good Yankees, we didn’t talk about everything we had lost. Instead, we tapped trees, hung buckets, strung up tubing and stacked the wood that would fuel the evaporator. These simple acts gave us a sense of purpose and brought us together at a time when the strain of caring for my grandmother, who had severe Alzheimer’s, threatened to tear the family apart completely. In that small sugar house, over stacks of pancakes smothered in hot syrup, we shared our stories – breaking with one tradition while upholding another. By age seven, Erica Holthausen was the official tour guide for maple syruping operations at Maple Grove Farm in North Guilford, Connecticut. A marketing mentor and freelance writer, this article first appeared as a part of a Food Memories book published as part of A Life in Context Project.

Comments are closed.

|

- Home

- About

- Maple Weekend

- Where to buy CT Maple Products - List By Town

- Connecticut Sugar Houses Map

- Membership & Joining

-

- MSPAC Annual Meeting - november

- Plymouth Maple Festival

- MSPAC Pre-Season Meeting - January

- Bright Acres Farm Open House

- Blue Slope Maple Festival

- Hebron Maple Festival

- Flanders Nature Center

- Stamford Museum's Maple Sugar Festival

- Ag Day at Capitol in Hartford

- Sweet WInd Farm Maple Festival

- Eastern CT Maple Festival

- Cookbook

- Contact

- Blog

- Home

- About

- Maple Weekend

- Where to buy CT Maple Products - List By Town

- Connecticut Sugar Houses Map

- Membership & Joining

-

- MSPAC Annual Meeting - november

- Plymouth Maple Festival

- MSPAC Pre-Season Meeting - January

- Bright Acres Farm Open House

- Blue Slope Maple Festival

- Hebron Maple Festival

- Flanders Nature Center

- Stamford Museum's Maple Sugar Festival

- Ag Day at Capitol in Hartford

- Sweet WInd Farm Maple Festival

- Eastern CT Maple Festival

- Cookbook

- Contact

- Blog